President Jimmy Carter 1977 1950's Fashion Poodle

Demonstrators march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965 to champion African American civil rights. Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click hither to improve this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- II. Kennedy and Cuba

- III. The Civil Rights Movement Continues

- 4. Lyndon Johnson'southward Great Society

- Five. The Origins of the Vietnam War

- VI. Culture and Activism

- VII. Beyond Civil Rights

- VIII. Decision

- IX. Main Sources

- Ten. Reference Cloth

I. Introduction

Perhaps no decade is so immortalized in American memory as the 1960s. Couched in the colorful rhetoric of peace and dear, complemented by stirring images of the civil rights motility, and fondly remembered for its music, art, and activism, the decade brought many people hope for a more inclusive, forward-thinking nation. But the decade was also plagued by strife, tragedy, and chaos. It was the decade of the Vietnam War, inner-urban center riots, and assassinations that seemed to symbolize the crushing of a new generation's idealism. A decade of struggle and disillusionment rocked by social, cultural, and political upheaval, the 1960s are remembered because so much changed, and because then much did non.

II. Kennedy and Cuba

The decade's political mural began with a watershed presidential ballot. Americans were captivated by the 1960 race between Republican vice president Richard Nixon and Autonomous senator John F. Kennedy, two candidates who pledged to move the nation forward and invigorate an economic system experiencing the worst recession since the Great Depression. Kennedy promised to use federal programs to strengthen the economy and accost pockets of longstanding poverty, while Nixon called for a reliance on private enterprise and reduction of government spending. Both candidates faced criticism as well; Nixon had to defend Dwight Eisenhower'south domestic policies, while Kennedy, who was attempting to become the first Catholic president, had to counteract questions virtually his organized religion and convince voters that he was experienced enough to lead.

One of the most notable events of the Nixon-Kennedy presidential campaign was their televised contend in September, the first of its kind between major presidential candidates. The fence focused on domestic policy and provided Kennedy with an of import moment to present himself as a composed, knowledgeable statesman. In contrast, Nixon, an experienced debater who faced higher expectations, looked sweaty and defensive. Radio listeners famously thought the two men performed equally well, but the Goggle box audience was much more impressed past Kennedy, giving him an reward in subsequent debates. Ultimately, the election was extraordinarily close; in the largest voter turnout in American history up to that point, Kennedy bested Nixon by less than one per centum point (34,227,096 to 34,107,646 votes). Although Kennedy's pb in electoral votes was more comfy at 303 to 219, the Democratic Party's victory did not translate in Congress, where Democrats lost a few seats in both houses. As a event, Kennedy entered office in 1961 without the mandate necessary to reach the ambitious agenda he would refer to equally the New Frontier.

Kennedy also faced foreign policy challenges. The United States entered the 1960s unaccustomed to stark foreign policy failures, having emerged from Globe War II as a global superpower before waging a Cold War confronting the Soviet Union in the 1950s. In the new decade, unsuccessful conflicts in Cuba and Vietnam would yield embarrassment, fear, and tragedy, stunning a nation that expected triumph and altering the way many thought of America'south office in international affairs.

On Jan 8, 1959, Fidel Castro and his revolutionary army initiated a new era of Cuban history. Having ousted the corrupt Cuban president Fulgencio Batista, who had fled Havana on New year's Eve, Castro and his rebel forces made their style triumphantly through the capital city'due south streets. The United states of america, which had long propped upwards Batista's corrupt authorities, had withdrawn back up and, initially, expressed sympathy for Castro's new government, which was immediately granted diplomatic recognition. But President Dwight Eisenhower and members of his assistants were wary. The new Cuban government soon instituted leftist economic policies centered on agrarian reform, country redistribution, and the nationalization of private enterprises. Republic of cuba's wealthy and middle-class citizens fled the island in droves. Many settled in Miami, Florida, and other American cities.

The relationship between Cuba and the United States deteriorated rapidly. On Oct 19, 1960, the Us instituted a virtually-total trade embargo to economically isolate the Cuban government, and in January 1961, the two nations broke off formal diplomatic relations. The Central Intelligence Bureau (CIA), acting under the mistaken belief that the Castro government lacked pop support and that Cuban citizens would revolt if given the opportunity, began to recruit members of the exile customs to participate in an invasion of the island. On April xvi, 1961, an invasion forcefulness consisting primarily of Cuban émigrés landed on Girón Beach at the Bay of Pigs. Cuban soldiers and civilians quickly overwhelmed the exiles, many of whom were taken prisoner. The Cuban government's success at thwarting the Bay of Pigs invasion did much to legitimize the new regime and was a tremendous embarrassment for the Kennedy assistants.

As the political human relationship between Cuba and the Usa disintegrated, the Castro government became more than closely aligned with the Soviet Spousal relationship. This strengthening of ties set the stage for the Cuban Missile Crisis, perchance the about dramatic foreign policy crunch in the history of the United States. In 1962, in response to the United states of america' longtime maintenance of a nuclear arsenal in Turkey and at the invitation of the Cuban government, the Soviet Wedlock deployed nuclear missiles in Cuba. On Oct 14, 1962, American spy planes detected the construction of missile launch sites, and on October 22, President Kennedy addressed the American people to alarm them to this threat. Over the course of the side by side several days, the world watched in horror as the Usa and the Soviet Union hovered on the brink of nuclear state of war. Finally, on Oct 28, the Soviet Union agreed to remove its missiles from Republic of cuba in exchange for a U.S. agreement to remove its missiles from Turkey and a formal pledge that the The states would not invade Republic of cuba, and the crisis was resolved peacefully.

![Protestors hold signs that read "President Kennedy Be Careful," "Let the UN Handle the Cuban Crisis!," "Peace or Perish," and "[unclear] your responsibility and give us peace."](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3c28465v-1000x1234.jpg)

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a time of bang-up feet in America. Viii hundred women demonstrated exterior the Un Building in 1962 to promote peace. Library of Congress.

Though the Cuban Missile Crisis temporarily halted the catamenia of Cuban refugees into the United States, emigration began again in earnest in the mid-1960s. In 1965, the Johnson administration and the Castro regime brokered a bargain that facilitated the reunion of families that had been separated by earlier waves of migration, opening the door for thousands to leave the island. In 1966 President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Cuban Adjustment Human action, a law assuasive Cuban refugees to get permanent residents. Over the course of the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Cubans left their homeland and built new lives in America.

Iii. The Civil Rights Motion Continues

So much of the free energy and character of the sixties emerged from the civil rights movement, which won its greatest victories in the early on years of the decade. The motility itself was irresolute. Many of the ceremonious rights activists pushing for school desegregation in the 1950s were eye-course and middle-aged. In the 1960s, a new student motion arose whose members wanted swifter changes in the segregated Due south. Confrontational protests, marches, boycotts, and sit-ins accelerated.1

The tone of the modern U.S. civil rights movement inverse at a Due north Carolina section shop in 1960, when four African American students participated in a demonstration at a whites-only lunch counter. The 1960 Greensboro sit-ins were typical. Activists sat at segregated lunch counters in an deed of defiance, refusing to leave until existence served and willing to be ridiculed, attacked, and arrested if they were non. This tactic drew resistance just forced the desegregation of Woolworth'southward department stores. It prompted copycat demonstrations across the Southward. The protests offered prove that student-led direct action could enact social change and established the civil rights movement's direction in the forthcoming years.two

The following year, ceremonious rights advocates attempted a bolder variation of a sit-in when they participated in the Liberty Rides. Activists organized interstate bus rides following a Supreme Court conclusion outlawing segregation on public buses and trains. The rides intended to exam the court's ruling, which many southern states had ignored. An interracial group of Liberty Riders boarded buses in Washington, D.C., with the intention of sitting in integrated patterns on the buses as they traveled through the Deep South. On the initial rides in May 1961, the riders encountered tearing resistance in Alabama. Angry mobs equanimous of KKK members attacked riders in Birmingham, burning 1 of the buses and beating the activists who escaped. Additional Freedom Rides launched through the summertime and generated national attention amid additional trigger-happy resistance. Ultimately, the Interstate Commerce Commission enforced integrated interstate buses and trains in November 1961.3

In the fall of 1961, ceremonious rights activists descended on Albany, a small city in southwest Georgia. Known for entrenched segregation and racial violence, Albany seemed an unlikely identify for Blackness Americans to rally and demand alter. The activists in that location, nonetheless, formed the Albany Movement, a coalition of civil rights organizers that included members of the Educatee Nonviolent Coordinating Commission (SNCC, or, "snick"), the SCLC, and the NAACP. But the movement was stymied by Albany police force chief Laurie Pritchett, who launched mass arrests but refused to engage in police brutality and bailed out leading officials to avert negative media attention. It was a peculiar scene, and a lesson for southern activists.4

The Albany Movement included elements of a Christian commitment to social justice in its platform, with activists stating that all people were "of equal worth" in God'south family and that "no man may discriminate confronting or exploit another." In many instances in the 1960s, Blackness Christianity propelled ceremonious rights advocates to action and demonstrated the significance of religion to the broader civil rights motion. King's rise to prominence underscored the role that African American religious figures played in the 1960s civil rights movement. Protesters sang hymns and spirituals equally they marched. Preachers rallied the people with messages of justice and promise. Churches hosted meetings, prayer vigils, and conferences on nonviolent resistance. The moral thrust of the movement strengthened African American activists and confronted white society by framing segregation equally a moral evil.v

Every bit the civil rights movement garnered more than followers and more than attention, white resistance stiffened. In October 1962, James Meredith became the get-go African American student to enroll at the Academy of Mississippi. Meredith's enrollment sparked riots on the Oxford campus, prompting President John F. Kennedy to send in U.S. Marshals and National Guardsmen to maintain order. On an evening known infamously as the Boxing of Ole Miss, segregationists clashed with troops in the middle of campus, resulting in two deaths and hundreds of injuries. Violence served as a reminder of the strength of white resistance to the civil rights movement, particularly in the realm of education.6

James Meredith, accompanied by U.S. Marshals, walks to grade at the University of Mississippi in 1962. Meredith was the first African American student admitted to the segregated university. Library of Congres.

The post-obit year, 1963, was perhaps the decade'southward near eventful year for civil rights. In April and May, the SCLC organized the Birmingham Entrada, a broad campaign of straight action aiming to topple segregation in Alabama's largest metropolis. Activists used business boycotts, sit-ins, and peaceful marches as part of the campaign. SCLC leader Martin Luther King Jr. was jailed, prompting his famous handwritten letter urging non just his nonviolent approach but agile confrontation to directly challenge injustice. The entrada further added to King's national reputation and featured powerful photographs and video footage of white constabulary officers using fire hoses and attack dogs on young African American protesters. It too yielded an agreement to desegregate public accommodations in the urban center: activists in Birmingham scored a victory for civil rights and drew international praise for the irenic arroyo in the face of police-sanctioned violence and bombings.vii

White resistance intensified. While much of the rhetoric surrounding the 1960s focused on a younger, more liberal generation's progressive ideas, conservatism maintained a strong presence on the American political scene. Few political figures in the decade embodied the working-form, conservative views held by millions of white Americans quite like George Wallace. Wallace's song stance on segregation was immortalized in his 1963 countdown address as Alabama governor with the phrase: "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!" Just every bit the ceremonious rights motion began to gain unprecedented strength, Wallace became the champion of the many white southerners opposed to the motion. Consequently, Wallace was one of the best examples of the very real opposition civil rights activists faced in the late twentieth century.8

As governor, Wallace loudly supported segregation. His efforts were symbolic, just they earned him national recognition as a political effigy willing to fight for what many southerners saw every bit their traditional manner of life. In June 1963, just five months after becoming governor, in his "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door," Wallace famously stood in the door of Foster Auditorium to protest integration at the University of Alabama. President Kennedy addressed the nation that evening, criticizing Wallace and calling for a comprehensive civil rights bill. A day afterward, civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated at his home in Jackson, Mississippi.

Alabama governor George Wallace stands defiantly at the door of the University of Alabama, blocking the attempted integration of the schoolhouse. Wallace became the most notorious pro-segregation politico of the 1960s, proudly proclaiming, in his 1963 inaugural address, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever." Library of Congress.

That summer, civil rights leaders organized the August 1963 March on Washington. The march called for, amongst other things, ceremonious rights legislation, school integration, an end to bigotry by public and private employers, job grooming for the unemployed, and a enhance in the minimum wage. On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Rex delivered his famous "I Accept a Dream" speech communication, an internationally renowned phone call for civil rights that raised the motion's profile to new heights and put unprecedented pressure level on politicians to laissez passer meaningful ceremonious rights legislation.9

This photo shows Martin Luther King Jr. and other Blackness civil rights leaders arm-in-arm with leaders of the Jewish community during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Wikimedia.

Kennedy offered support for a ceremonious rights bill, just southern resistance was intense and Kennedy was unwilling to expend much political capital on it. And so the bill stalled in Congress. And so, on Nov 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. The nation's youthful, popular president was gone. Vice President Lyndon Johnson lacked Kennedy'due south youth, his charisma, his popularity, and his aristocratic upbringing, but no one knew Washington amend and no one before or since fought harder and more successfully to laissez passer meaningful civil rights legislation. Raised in poverty in the Texas Hill State, Johnson scratched and clawed his way up the political ladder. He was both ruthlessly ambitious and keenly conscious of poverty and injustice. He idolized Franklin Roosevelt whose New Deal had brought improvements for the impoverished central Texans Johnson grew upwards with.

President Lyndon Johnson, then, an old white southerner with a thick Texas drawl, embraced the civil rights move. He took Kennedy's stalled civil rights bill, ensured that information technology would have teeth, and navigated it through Congress. The following summer he signed the Ceremonious Rights Human activity of 1964, widely considered to exist among the most important pieces of civil rights legislation in American history. The comprehensive act barred segregation in public accommodations and outlawed bigotry based on race, ethnicity, gender, and national or religious origin.

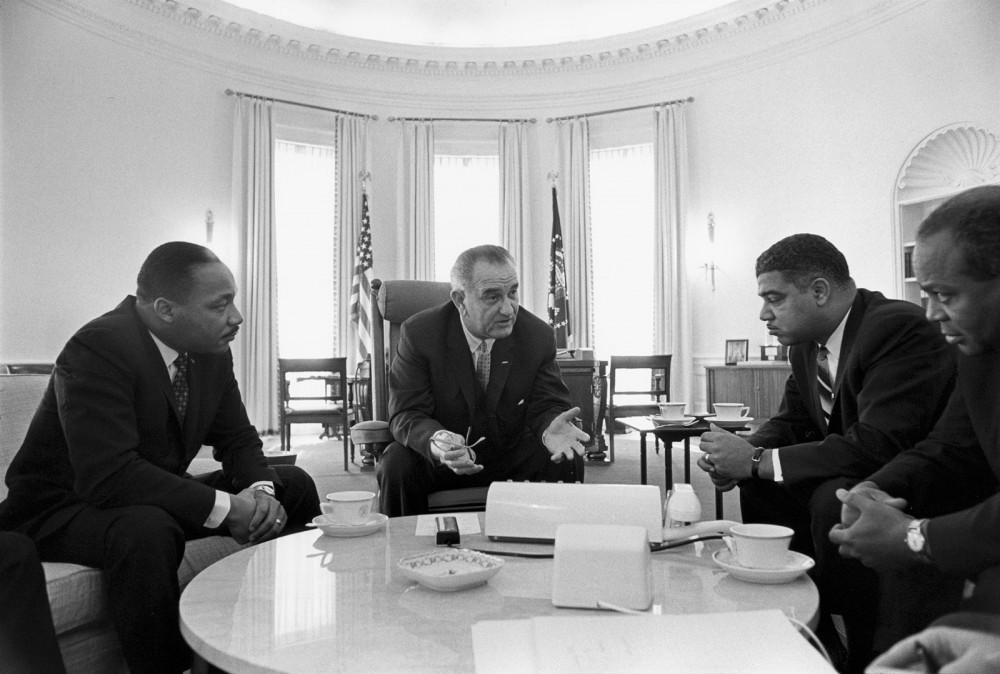

Lyndon B. Johnson sits with Ceremonious Rights Leaders in the White House. One of Johnson'southward greatest legacies would be his staunch support of civil rights legislation. Wikimedia.

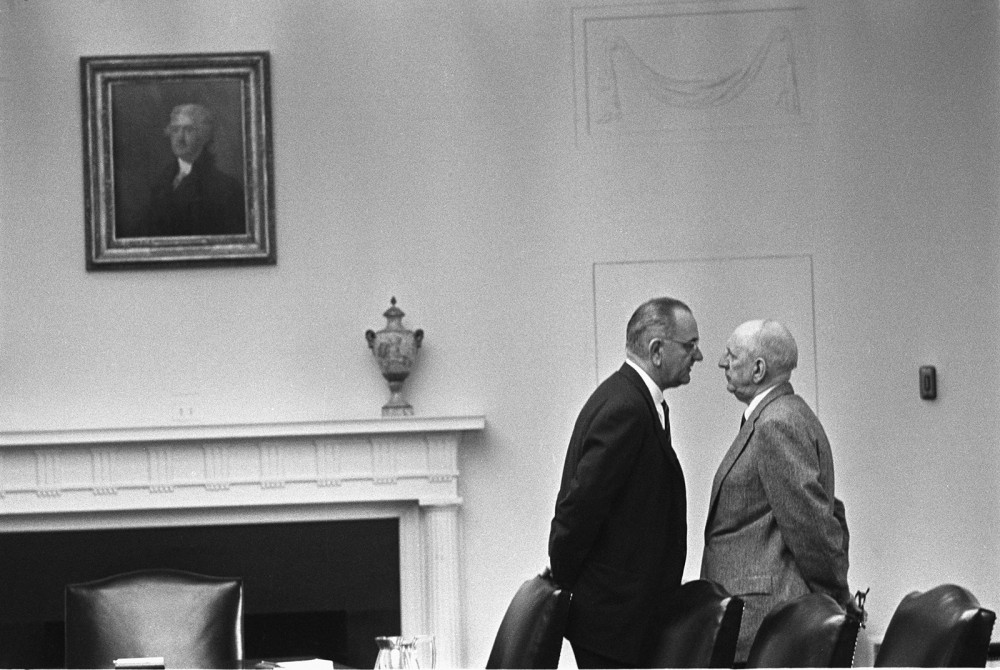

Johnson gives Senator Richard Russell the famous "Johnson Handling." Yoichi R. Okamoto, Photograph of Lyndon B. Johnson pressuring Senator Richard Russell, December 17, 1963. Wikimedia.

The ceremonious rights motion created space for political leaders to pass legislation, and the motility connected pushing forward. Straight activeness continued through the summer of 1964, equally pupil-run organizations like SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) helped with the Freedom Summertime in Mississippi, a drive to annals African American voters in a state with an ugly history of discrimination. Freedom Summer campaigners ready schools for African American children. Even with progress, intimidation and violent resistance against civil rights connected, specially in regions with longstanding traditions of segregation.10

In March 1965, activists attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on behalf of local African American voting rights. In a narrative that had go familiar, "Bloody Sunday" featured peaceful protesters attacked by white law enforcement with batons and tear gas. Afterward they were turned away violently a second fourth dimension, marchers finally made the fifty-mile trek to the state capitol later in the month. Coverage of the start march prompted President Johnson to present the beak that became the Voting Rights Act of 1965, an act that abolished voting discrimination in federal, state, and local elections. In 2 consecutive years, landmark pieces of legislation had assaulted de jure (by law) segregation and disenfranchisement.11

Five leaders of the Ceremonious Rights Movement in 1965. From left: Bayard Rustin, Andrew Immature, North.Y. Congressman William Ryan, James Farmer, and John Lewis. Library of Congress.

IV. Lyndon Johnson's Great Society

On a May morning in 1964, President Johnson laid out a sweeping vision for a packet of domestic reforms known as the Great Society. Speaking before that year's graduates of the University of Michigan, Johnson called for "an cease to poverty and racial injustice" and challenged both the graduates and American people to "enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization." At its eye, he promised, the Nifty Society would uplift racially and economically disfranchised Americans, too long denied access to federal guarantees of equal democratic and economic opportunity, while simultaneously raising all Americans' standards and quality of life.12

The Great Gild's legislation was breathtaking in scope, and many of its programs and agencies are nonetheless with usa today. Most importantly, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 codification federal support for many of the civil rights movement'south goals by prohibiting chore bigotry, abolishing the segregation of public accommodations, and providing vigorous federal oversight of southern states' election laws in order to guarantee minority access to the election. Ninety years after Reconstruction, these measures finer ended Jim Crow.

In addition to ceremonious rights, the Smashing Society took on a range of quality-of-life concerns that seemed all of a sudden solvable in a society of such affluence. It established the first federal food stamp program. Medicare and Medicaid would ensure access to quality medical care for the aged and poor. In 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Instruction Act was the first sustained and meaning federal investment in public didactics, totaling more than $1 billion. Significant funds were poured into colleges and universities. The Great Guild also established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, federal investments in arts and letters that fund American cultural expression to this day.

While these programs persisted and fifty-fifty thrived, in the years immediately following this flurry of legislative activity, the national conversation surrounding Johnson'south domestic agenda largely focused on the $iii billion spent on War on Poverty programming within the Great Club'southward Economic Opportunity Human activity (EOA) of 1964. No EOA program was more controversial than Customs Action, considered the cornerstone antipoverty program. Johnson's antipoverty planners felt that the primal to uplifting disfranchised and impoverished Americans was involving poor and marginalized citizens in the actual administration of poverty programs, what they called "maximum viable participation." Community Action Programs would requite disfranchised Americans a seat at the table in planning and executing federally funded programs that were meant to benefit them—a significant body of water change in the nation's efforts to confront poverty, which had historically relied on local political and business organisation elites or charitable organizations for administration.13

In fact, Johnson himself had never conceived of poor Americans running their own poverty programs. While the president's rhetoric offered a stirring vision of the futurity, he had singularly old-school notions for how his poverty policies would work. In dissimilarity to "maximum viable participation," the president imagined a second New Bargain: local elite-run public works camps that would instill masculine virtues in unemployed young men. Customs Action about entirely bypassed local administrations and sought to build grassroots civil rights and community advocacy organizations, many of which had originated in the broader ceremonious rights movement. Despite widespread back up for almost Corking Social club programs, the War on Poverty increasingly became the focal bespeak of domestic criticisms from the left and right. On the left, frustrated Americans recognized the president'due south resistance to further empowering poor minority communities and also assailed the growing war in Vietnam, the cost of which undercut domestic poverty spending. Equally racial unrest and violence swept beyond urban centers, critics from the right lambasted federal spending for "unworthy" citizens.

Johnson had secured a series of meaningful civil rights laws, simply then things began to stall. Days after the ratification of the Voting Rights Act, race riots broke out in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. Rioting in Watts stemmed from local African American frustrations with residential segregation, police force brutality, and racial profiling. Waves of riots rocked American cities every summer thereafter. Particularly destructive riots occurred in 1967—ii summers afterwards—in Newark and Detroit. Each resulted in deaths, injuries, arrests, and millions of dollars in property harm. In spite of Black achievements, problems persisted for many African Americans. The phenomenon of "white flight"—when whites in metropolitan areas fled metropolis centers for the suburbs—oftentimes resulted in resegregated residential patterns. Limited admission to economical and social opportunities in urban areas bred discord. In addition to reminding the nation that the civil rights move was a complex, ongoing event without a physical endpoint, the unrest in northern cities reinforced the notion that the struggle did not occur solely in the South. Many Americans besides viewed the riots as an indictment of the Great Society, President Johnson'due south sweeping agenda of domestic programs that sought to remedy inner-city ills by offering meliorate admission to education, jobs, medical care, housing, and other forms of social welfare. The civil rights movement was never the aforementioned.14

The Civil Rights Acts, the Voting Rights Acts, and the War on Poverty provoked bourgeois resistance and were catalysts for the rising of Republicans in the South and West. However, subsequent presidents and Congresses accept left intact the bulk of the Slap-up Society, including Medicare and Medicaid, food stamps, federal spending for arts and literature, and Head Commencement. Fifty-fifty Community Action Programs, so fraught during their few short years of activity, inspired and empowered a new generation of minority and poverty community activists who had never before felt, as 1 put it, that "this government is with the states."15

V. The Origins of the Vietnam War

American involvement in the Vietnam War began during the postwar menstruum of decolonization. The Soviet Wedlock backed many nationalist movements across the globe, but the United States feared the expansion of communist influence and pledged to confront any revolutions aligned against Western capitalism. The Domino Theory—the idea that if a country savage to communism, and so neighboring states would soon follow—governed American foreign policy. After the communist takeover of China in 1949, the Us financially supported the French military'due south effort to retain control over its colonies in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Lao people's democratic republic.

Betwixt 1946 and 1954, France fought a counterinsurgency entrada against the nationalist Viet Minh forces led past Ho Chi Minh. The United States assisted the French war effort with funds, arms, and advisors, but it was not enough. On the eve of the Geneva Peace Conference in 1954, Viet Minh forces defeated the French army at Dien Bien Phu. The briefing temporarily divided Vietnam into two separate states until Un-monitored elections occurred. But the United States feared a communist electoral victory and blocked the elections. The temporary partition became permanent. The Usa established the Democracy of Vietnam, or South Vietnam, with the U.Due south.-backed Ngo Dinh Diem as prime number minister. Diem, who had lived in the United States, was a committed anticommunist.

Diem's regime, however, and its Army of the Commonwealth of Vietnam (ARVN) could not contain the communist insurgency seeking the reunification of Vietnam. The Americans provided weapons and support, but despite a clear numerical and technological advantage, S Vietnam stumbled before insurgent Vietcong (VC) units. Diem, a decadent leader propped upward by the American government with little domestic back up, was assassinated in 1963. A merry-go-round of armed forces dictators followed as the situation in South Vietnam continued to deteriorate. The American public, though, remained largely unaware of Vietnam in the early 1960s, even equally President John F. Kennedy deployed some sixteen thousand military advisors to assistance Southward Vietnam suppress a domestic communist insurgency.16

This all changed in 1964. On August 2, the USS Maddox reported incoming fire from North Vietnamese ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. Although the details of the incident are controversial, the Johnson administration exploited the event to provide a pretext for escalating American interest in Vietnam. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting President Johnson the authority to deploy the American military to defend South Vietnam. U.S. Marines landed in Vietnam in March 1965, and the American basis state of war began.

American forces under General William Westmoreland were tasked with defending Southward Vietnam against the insurgent VC and the regular North Vietnamese Army (NVA). But no matter how many troops the Americans sent or how many bombs they dropped, they could not win. This was a different kind of state of war. Progress was non measured by cities won or territory taken but by body counts and kill ratios. Although American officials like Westmoreland and secretarial assistant of defense Robert McNamara claimed a communist defeat was on the horizon, by 1968 one-half a million American troops were stationed in Vietnam, most xx thousand had been killed, and the war was still no closer to being won. Protests, which would provide the properties for the American counterculture, erupted beyond the country.

VI. Culture and Activism

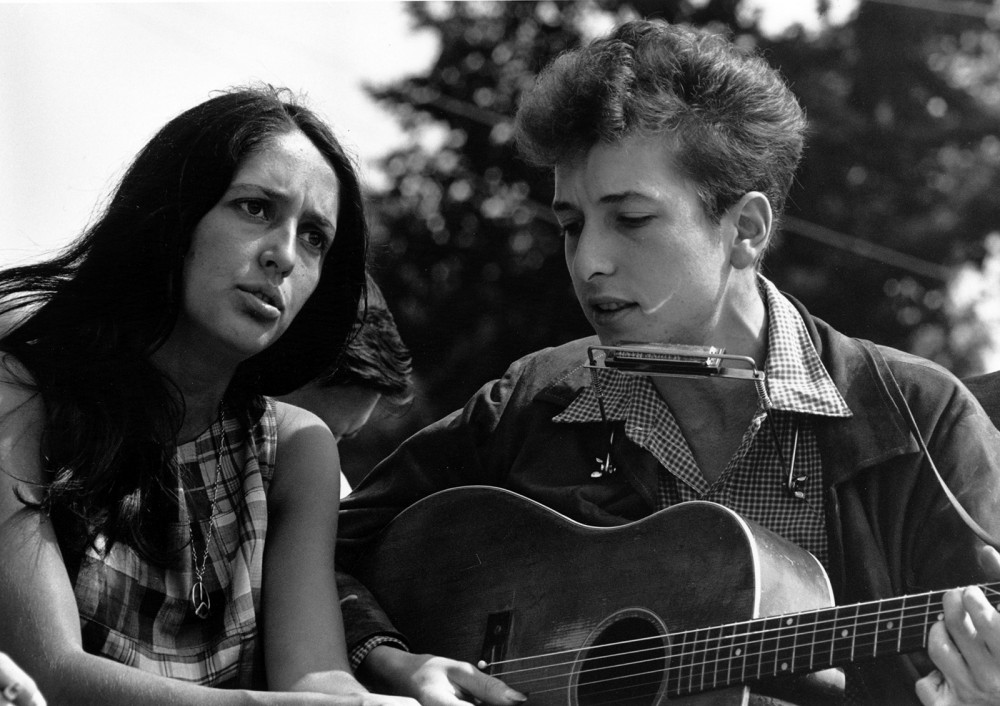

Epitomizing the folk music and protest culture of 1960s youth, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan are pictured hither singing together at the March on Washington in 1963. Wikimedia.

The 1960s wrought enormous cultural change. The Us that entered the decade looked and sounded little like the one that left it. Rebellion rocked the supposedly hidebound conservatism of the 1950s as the youth counterculture became mainstream. Native Americans, Chicanos, women, and environmentalists participated in movements demonstrating that rights activism could exist applied to ethnicity, gender, and nature. Fifty-fifty established religious institutions such equally the Catholic Church underwent transformations, emphasizing freedom and tolerance. In each instance, the decade brought substantial progress and evidence that activism remained fluid and unfinished.

Much of the counterculture was filtered through pop civilisation and consumption. The fifties consumer civilisation still saturated the state, and advertisers continued to entreatment to teenagers and the expanding youth market. During the 1960s, though, advertisers looked to a growing counterculture to sell their products. Popular culture and popular advertizement in the 1950s had promoted an ethos of "fitting in" and buying products to conform. The new countercultural ethos touted individuality and rebellion. Some advertisers were subtle; ads for Volkswagens (VWs) acknowledged the flaws and strange look of their cars. One ad read, "Presenting America'south slowest fastback," which "won't get over 72 mph even though the speedometer shows a wildly optimistic superlative speed of xc." Another stated, "And if you run out of gas, information technology's easy to push." By marketing the car'due south flaws and reframing them as positive qualities, the advertisers commercialized young people's resistance to commercialism, while simultaneously positioning the VW as a car for those wanting to stand out in a crowd. A more obviously countercultural ad for the VW Bug showed two cars: one black and 1 painted multicolor in the hippie style; the contrasting captions read, "We do our thing," and "You lot do yours."

Companies marketed their products as countercultural in and of themselves. Ane of the more than obvious examples was a 1968 advertisement from Columbia Records, a hugely successful record characterization since the 1920s. The advert pictured a group of stock rebellious characters—a shaggy-haired white hippie, a buttoned-upwardly Beat, two biker types, and a Black jazz man sporting an Afro—in a prison cell. The counterculture had been busted, the ad states, merely "the man tin can't bust our music." Only ownership records from Columbia was an act of rebellion, one that brought the buyer closer to the counterculture figures portrayed in the ad.17

Simply it wasn't merely advertising: the culture was changing and changing rapidly. Conservative cultural norms were falling everywhere. The dominant style of women's fashion in the 1950s, for example, was the poodle skirt and the sweater, tight-waisted and buttoned upward. The 1960s ushered in an era of much less restrictive wearable. Capri pants became popular casual wearable. Skirts became shorter. When Mary Quant invented the miniskirt in 1964, she said it was a garment "in which you could move, in which y'all could run and jump."18 By the late 1960s, the hippies' more androgynous wait became trendy. Such trends bespoke the new pop ethos of the 1960s: freedom, rebellion, and individuality.

In a decade plagued by social and political instability, the American counterculture too sought psychedelic drugs equally its remedy for alienation. For middle-grade white teenagers, gild had become stagnant and bureaucratic. The New Left, for instance, arose on higher campuses frustrated with the lifeless bureaucracies that they believed strangled true liberty. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) began its life as a drug used primarily in psychological research before trickling down into higher campuses and out into society at large. The counterculture'southward notion that American stagnation could exist remedied by a spiritual-psychedelic experience drew heavily from psychologists and sociologists. The popularity of these drugs as well spurred a political backlash. By 1966, enough incidents had been connected to LSD to spur a Senate hearing on the drug, and newspapers were reporting that hundreds of LSD users had been admitted to psychiatric wards.

The counterculture conquered popular culture. Stone 'north' whorl, liberalized sexuality, an comprehend of diverseness, recreational drug use, unalloyed idealism, and pure earnestness marked a new generation. Criticized past conservatives as culturally dangerous and by leftists as empty narcissism, the youth civilisation nevertheless dominated headlines and steered American culture. Mayhap one hundred k youth descended on San Francisco for the utopic promise of 1967's Summer of Beloved. 1969's Woodstock concert in New York became autograph for the new youth culture and its mixture of politics, protest, and personal fulfillment. While the ascendance of the hippies would exist both exaggerated and short-lived, and while Vietnam and Richard Nixon shattered much of its idealism, the counterculture'south liberated social norms and its embrace of personal fulfillment still ascertain much of American civilization.

VII. Across Civil Rights

Despite substantial legislative achievements, frustrations with the wearisome pace of alter grew. Tensions continued to mount in cities, and the tone of the ceremonious rights movement changed all the same once again. Activists became less conciliatory in their calls for progress. Many embraced the more militant message of the burgeoning Blackness Power Movement and Malcolm Ten, a Nation of Islam (NOI) minister who encouraged African Americans to pursue freedom, equality, and justice past "any means necessary." Prior to his death in 1965, Malcolm X and the NOI emerged equally the radical alternative to the racially integrated, largely Protestant approach of Martin Luther Male monarch Jr. Malcolm advocated armed resistance in defence force of the safety and well-existence of Black Americans, stating, "I don't call information technology violence when it's self-defence, I call it intelligence." For his office, Rex and leaders from more than mainstream organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League criticized both Malcolm X and the NOI for what they perceived to be racial demagoguery. Rex believed Malcolm X's speeches were a "great disservice" to Black Americans, claiming that they lamented the problems of African Americans without offering solutions. The differences between King and Malcolm X represented a core ideological tension that would inhabit Black political thought throughout the 1960s and 1970s.19

Similar Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois before them, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm Ten, pictured here in 1964, represented different strategies to accomplish racial justice. Library of Congress.

By the tardily 1960s, SNCC, led by figures such equally Stokely Carmichael, had expelled its white members and shunned the interracial endeavor in the rural South, focusing instead on injustices in northern urban areas. After President Johnson refused to take up the crusade of the Blackness delegates in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, SNCC activists became frustrated with institutional tactics and turned away from the system's founding principle of nonviolence. This evolving, more aggressive movement chosen for African Americans to play a dominant function in cultivating Black institutions and articulating Blackness interests rather than relying on interracial, moderate approaches. At a June 1966 ceremonious rights march, Carmichael told the crowd, "What nosotros gonna offset saying now is blackness power!"20 The slogan not only resonated with audiences, it also stood in straight contrast to King'south "Freedom Now!" campaign. The political slogan of Black power could encompass many meanings, but at its cadre information technology stood for the self-determination of Black people in political, economic, and social organizations.

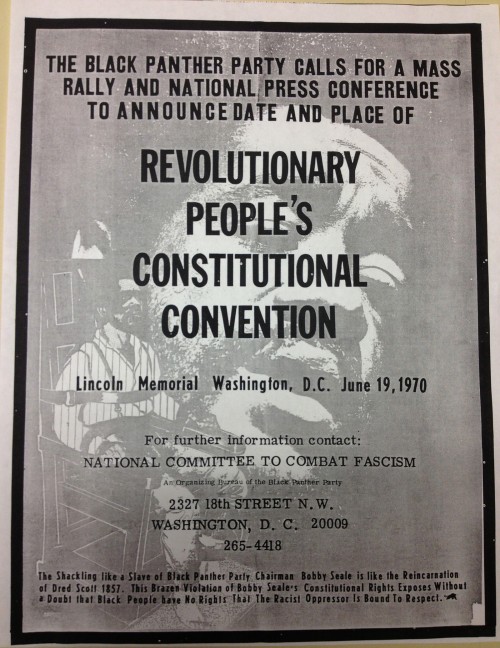

The Blackness Panther Party used radical and incendiary tactics to bring attention to the continued oppression of Black Americans. This 1970 poster captures their outlook. Wikimedia.

Carmichael asserted that "blackness power means black people coming together to course a political strength."21 To others it also meant violence. In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. The Black Panthers became the standard-bearers for direct action and self-defence, using the concept of decolonization in their drive to liberate Black communities from white power structures. The revolutionary organization also sought reparations and exemptions for Black men from the war machine draft. Citing law brutality and racist governmental policies, the Blackness Panthers aligned themselves with the "other people of color in the globe" confronting whom America was fighting abroad. Although it was perhaps most well known for its open display of weapons, military-mode dress, and Blackness nationalist behavior, the party's x-Point Plan too included employment, housing, and instruction. The Black Panthers worked in local communities to run "survival programs" that provided food, clothing, medical handling, and drug rehabilitation. They focused on modes of resistance that empowered Blackness activists on their own terms.22

Simply African Americans weren't the only Americans struggling to assert themselves in the 1960s. The successes of the civil rights movement and growing grassroots activism inspired countless new movements. In the summer of 1961, for instance, frustrated Native American university students founded the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) to draw attending to the plight of Indigenous Americans. In the Pacific Northwest, the council advocated for tribal fisherman to retain immunity from conservation laws on reservations and in 1964 held a series of "fish-ins": activists and celebrities cast nets and waited for the police to abort them.23 The NIYC's militant rhetoric and use of direct activeness marked the commencement of what was called the Red Power movement, an intertribal move designed to draw attending to Native issues and to protestation discrimination. The American Indian Motility (AIM) and other activists staged dramatic demonstrations. In November 1969, dozens began a yr-and-a-half-long occupation of the abandoned Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. In 1973, hundreds occupied the town of Wounded Human knee, Due south Dakota, site of the infamous 1890 massacre, for several months.24

Meanwhile, the Chicano movement in the 1960s emerged out of the broader Mexican American civil rights motility of the post–World State of war 2 era. The discussion Chicano was initially considered a derogatory term for Mexican immigrants, until activists in the 1960s reclaimed the term and used it equally a goad to campaign for political and social change among Mexican Americans. The Chicano movement confronted discrimination in schools, politics, agriculture, and other formal and informal institutions. Organizations like the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA) and the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDF) buoyed the Chicano movement and patterned themselves after similar influential groups in the African American civil rights motion.25

Cesar Chavez became the most well-known effigy of the Chicano movement, using irenic tactics to campaign for workers' rights in the grape fields of California. Chavez and activist Dolores Huerta founded the National Farm Workers Association, which eventually merged and became the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA). The UFWA fused the causes of Chicano and Filipino activists protesting the subpar working conditions of California farmers on American soil. In improver to embarking on a hunger strike and a boycott of table grapes, Chavez led a three-hundred-mile march in March and April 1966 from Delano, California, to the state capital of Sacramento. The pro-labor campaign garnered the national spotlight and the back up of prominent political figures such as Robert Kennedy. Today, Chavez's birthday (March 31) is observed as a federal holiday in California, Colorado, and Texas.

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was another activist whose calls for Chicano self-determination resonated long past the 1960s. A former boxer and Denver native, Gonzales founded the Crusade for Justice in 1966, an organization that would institute the kickoff annual Chicano Liberation Twenty-four hour period at the National Chicano Youth Briefing. The conference besides yielded the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, a Chicano nationalist manifesto that reflected Gonzales's vision of Chicanos as a unified, historically grounded, all-encompassing grouping fighting confronting discrimination in the United States. By 1970, the Texas-based La Raza Unida political party had a stiff foundation for promoting Chicano nationalism and continuing the entrada for Mexican American ceremonious rights.26

The 1966 Rio Grande Valley Farm Workers March ("La Marcha"). August 27, 1966. The Academy of Texas-San Antonio Libraries' Special Collections (MS 360: E-0012-187-D-xvi)

The feminist movement also grew in the 1960s. Women were active in both the ceremonious rights motility and the labor move, merely their increasing awareness of gender inequality did not find a receptive audience amid male leaders in those movements. In the 1960s, then, many of these women began to form a movement of their own. Shortly the country experienced a groundswell of feminist consciousness.

An older generation of women who preferred to work within state institutions figured prominently in the early role of the decade. When John F. Kennedy established the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in 1961, old first lady Eleanor Roosevelt headed the effort. The committee'southward official report, a cocky-declared "invitation to activity," was released in 1963. Finding discriminatory provisions in the police and practices of industrial, labor, and governmental organizations, the commission advocated for "changes, many of them long overdue, in the conditions of women's opportunity in the U.s.a.."27 Modify was recommended in areas of employment practices, federal tax and do good policies affecting women'south income, labor laws, and services for women as wives, mothers, and workers. This telephone call for action, if heeded, would ameliorate the types of discrimination primarily experienced by middle-grade and elite white working women, all of whom were used to advocating through institutional structures similar government agencies and unions.28 The specific concerns of poor and nonwhite women lay largely beyond the telescopic of the report.

Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique hit bookshelves the same year the commission released its report. Friedan had been active in the union motion and was past this time a mother in the new suburban landscape of postwar America. In her volume, Friedan labeled the "problem that has no name," and in doing and then helped many white middle-class American women come to see their dissatisfaction as housewives not as something "wrong with [their] wedlock, or [themselves]," but instead as a social trouble experienced by millions of American women. Friedan observed that there was a "discrepancy between the reality of our lives every bit women and the image to which we were trying to suit, the image I phone call the feminine mystique." No longer would women allow society to blame the "problem that has no name" on a loss of femininity, too much education, or too much female independence and equality with men.29

The 1960s also saw a different group of women pushing for alter in government policy. Mothers on welfare began to form local advocacy groups in addition to the National Welfare Rights Organization, founded in 1966. Mostly African American, these activists fought for greater benefits and more control over welfare policy and implementation. Women like Johnnie Tillmon successfully advocated for larger grants for school apparel and household equipment in addition to gaining due process and fair administrative hearings prior to termination of welfare entitlements.

Yet another mode of feminist activism was the formation of consciousness-raising groups. These groups met in women'due south homes and at women'south centers, providing a rubber environment for women to discuss everything from experiences of gender discrimination to pregnancy, from relationships with men and women to self-prototype. The goal of consciousness-raising was to increase self-awareness and validate the experiences of women. Groups framed such private experiences as examples of lodge-wide sexism, and claimed that "the personal is political."30 Consciousness-raising groups created a wealth of personal stories that feminists could employ in other forms of activism and crafted networks of women from which activists could mobilize support for protests.

The stop of the decade was marked by the Women'due south Strike for Equality, jubilant the fiftieth ceremony of women's right to vote. Sponsored by the National Organisation for Women (NOW), the 1970 protest focused on employment discrimination, political equality, abortion, gratuitous childcare, and equality in matrimony. All of these issues foreshadowed the backfire confronting feminist goals in the 1970s. Non only would feminism face opposition from other women who valued the traditional homemaker function to which feminists objected, the feminist movement would too fracture internally as minority women challenged white feminists' racism and lesbians vied for more prominence inside feminist organizations.

The women'south movement stalled during the 1930s and 1940s, but past the 1960s it was back in full forcefulness. Inspired by the civil rights move and fed up with gender discrimination, women took to the streets to demand their rights as American citizens. Here, women march during the "Women'southward Strike for Equality," a nationwide protest launched on the 50th ceremony of women's suffrage. Photograph, Baronial 26, 1970. Library of Congress.

American environmentalism's pregnant gains during the 1960s emerged in part from Americans' recreational use of nature. Postwar Americans backpacked, went to the beach, fished, and joined birding organizations in greater numbers than always earlier. These experiences, forth with increased formal pedagogy, made Americans more aware of threats to the environment and, consequently, to themselves. Many of these threats increased in the postwar years as developers bulldozed open space for suburbs and new hazards emerged from industrial and nuclear pollutants.

By the time that biologist Rachel Carson published her landmark volume, Silent Spring, in 1962, a nascent environmentalism had emerged in America. Silent Spring stood out as an unparalleled argument for the interconnectedness of ecological and human wellness. Pesticides, Carson argued, also posed a threat to human wellness, and their overuse threatened the ecosystems that supported food production. Carson'south argument was compelling to many Americans, including President Kennedy, only was virulently opposed by chemical industries that suggested the book was the production of an emotional woman, not a scientist.31

After Silent Jump, the social and intellectual currents of environmentalism continued to expand apace, culminating in the largest demonstration in history, Earth Day, on April 22, 1970, and in a decade of lawmaking that significantly restructured American authorities. Fifty-fifty earlier the massive gathering for World Solar day, lawmakers from the local to the federal level had pushed for and achieved regulations to clean upwardly the air and water. President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Deed into law in 1970, requiring ecology touch on statements for any project directed or funded by the federal government. He also created the Environmental Protection Bureau, the first agency charged with studying, regulating, and disseminating noesis about the environment. A raft of laws followed that were designed to offering increased protection for air, water, endangered species, and natural areas.

The decade'southward activism manifested across the world. It even afflicted the Cosmic Church. The 2d Vatican Council, called by Pope John XXIII to modernize the church and bring information technology in closer dialogue with the non-Catholic world, operated from 1962 to 1965, when information technology proclaimed multiple reforms, including the vernacular mass (mass in local languages, rather than in Latin) and a greater role for laypeople, and specially women, in the Church. Many Catholic churches adopted more informal, contemporary styles. Many conservative Catholics recoiled at what they perceived every bit rapid and unsafe changes, but Vatican Ii's reforms in many ways created the modern Catholic Church.

VIII. Decision

In 1969, Americans hailed the moon landing as a profound victory in the space race confronting the Soviet Union. This landmark achievement fulfilled the promise of the belatedly John F. Kennedy, who had alleged in 1961 that the Usa would put a homo on the moon past the end of the decade. But while Neil Armstrong said his steps marked "one behemothic leap for mankind," and Americans marveled at the achievement, the brief moment of wonder but punctuated years of turmoil. The Vietnam State of war disillusioned a generation, riots rocked cities, protests hitting campuses, and assassinations robbed the nation of many of its leaders. The frontward-thinking spirit of a complex decade had waned. Uncertainty loomed.

IX. Primary Sources

i. Barry Goldwater, Republican Nomination Acceptance Speech (1964)

In 1964, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona accepted the Republican Party's nomination for the presidency. In his speech, Goldwater refused to apologize for his strict bourgeois politics. "Extremism in the defence of liberty is no vice," he said, and "moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue."

two. Lyndon Johnson on Voting Rights and the American Promise (1965)

On March 15, 1965, Lyndon Baines Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress to push for the Voting Rights Act. In his oral communication, Johnson not but advocated policy, he borrowed the language of the civil rights movement and tied the movement to American history.

three. Lyndon Johnson, Howard Academy Kickoff Address (1965)

On June 4, 1965, President Johnson delivered the commencement address at Howard University, the nation's well-nigh prominent historically Blackness academy. In his address, Johnson explained why "opportunity" was not enough to ensure the civil rights of disadvantaged Americans.

4. National Organization for Women, "Argument of Purpose" (1966)

The National Organization for Women was founded in 1966 by prominent American feminists, including Betty Friedan, Shirley Chisolm, and others. The organization's "statement of purpose" laid out the goals of the organisation and the targets of its feminist vision.

v. George Grand. Garcia, Vietnam Veteran, Oral Interview (2012/1969)

In 2012, George Garcia sat downwards to be interviewed most his experiences equally a corporal in the United States Marine Corps during the Vietnam War. Alternating between English and Spanish, Garcia told of early life in Brownsville, Texas, his time every bit a U.Due south. Marine in Vietnam, and his feel coming abode from the war.

6. The Port Huron Statement (1962)

The Port Huron Statement was a 1962 manifesto past the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), written primarily by student activist Tom Hayden, that proposed a new course of "participatory democracy" to rescue mod society from subversive militarism and cultural alienation.

7. Fannie Lou Hamer: Testimony at the Democratic National Convention 1964

Civil rights activists struggled against the repressive violence of Mississippi's racial government. State NAACP head Medger Evers was murdered in 1963. Freedom Summertime activists tried to register Black voters in 1964. Three disappeared and were found murdered. The Mississippi Autonomous Party connected to disfranchise the state's African American voters. Civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Autonomous Political party (MFDP) and traveled to the Autonomous National Convention in 1964 to need that the MFDP's delegates, rather than the all-white Mississippi Democratic Political party delegates, be seated in the convention. Although unsuccessful, her moving testimony was broadcast on national telly and drew further attention to the plight of African Americans in the South.

viii. Selma March (1965)

Civil rights activists protested against the injustice of segregation in a variety of means. Here, in 1965, marchers, some carrying American flags, march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to champion African American voting rights.

9. LBJ and Civil Rights Leaders (1964)

As ceremonious rights demonstrations rocked the American South, civil rights legislation made its manner through Washington D.C. Here, President Lyndon B. Johnson sits with ceremonious rights leaders in the White Firm.

10. Women'due south Liberation March (1970)

American popular feminism accelerated throughout the 1960s. The slogan "Women'due south Liberation" accompanied a growing women's motion but too alarmed conservative Americans. In this 1970 photograph, women march during the "Women's Strike for Equality," a nationwide protestation launched on the 50th anniversary of women'due south suffrage, carrying signs reading, "Women Demand Equality," "I'm a Second Class Citizen," and "Women's Liberation."

X. Reference Material

This affiliate was edited by Samuel Abramson, with content contributions by Samuel Abramson, Marsha Barrett, Brent Cebul, Michell Chresfield, William Cossen, Jenifer Dodd, Michael Falcone, Leif Fredrickson, Jean-Paul de Guzman, Jordan Loma, William Kelly, Lucie Kyrova, Maria Montalvo, Emily Prifogle, Ansley Quiros, Tanya Roth, and Robert Thompson.

Recommended citation: Samuel Abramson et al., "The Sixties," Samuel Abramson, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–1963. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

- ———. Colonnade of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998.

- Breines, Winifred. The Problem Between Us: An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in the Feminist Move. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Brick, Howard. The Historic period of Contradictions: American Idea and Culture in the 1960s. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

- Brown-Nagin, Tomiko. Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Ceremonious Rights Mov ement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Printing, 1981.

- Abrasion, William. Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Liberty. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Dallek, Robert. Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961–1973. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- D'Emilio, John. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the U.s.a., 1940–1970. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1983.

- Echols, Alice. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975. Minneapolis: Academy of Minnesota Press, 1989.

- Gitlin, Todd. The Sixties: Years of Promise, Days of Rage. New York: Runted Books, 1987.

- Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. "The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past." Periodical of American History 91 (March 2005): 1233–1263.

- Isserman, Maurice. If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the One-time Left and the Birth of the New Left. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

- Johnson, Troy R. The American Indian Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Cherry-red Power and Cocky-Determination. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Printing, 2008.

- Joseph, Peniel. Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Blackness Power in America. New York: Holt, 2006.

- Kazin, Michael, and Maurice Isserman. America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2007.

- McGirr, Lisa. Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Correct. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2001.

- Orleck, Annelise. Storming Caesar's Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty. New York: Buoy Books, 2005.

- Patterson, James T. America's Struggle Against Poverty in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Patterson, James T. G Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1996.

- Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- Ransby, Barbara. Ella Bakery and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Autonomous Vision. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Printing, 2000.

- Robnett, Belinda. How Long? How Long?: African American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights. New York: Oxford University Printing, 2000.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2005.

Notes

- For the major events of the civil rights motility, see Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988); Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998); and Taylor Branch, At Canaan's Edge: America in the Rex Years, 1965–68 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007). [↩]

- Branch, Parting the Waters. [↩]

- Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice (New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2006). [↩]

- Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Blackness Enkindling of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980); Adam Fairclough, To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference & Martin Luther Rex (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987). [↩]

- David Fifty. Chappell, A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (Chapel Loma: University of North Carolina Press, 2005). [↩]

- Co-operative, Parting the Waters. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Dan T. Carter, The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2000). [↩]

- Branch, Parting the Waters. [↩]

- Branch, Pillar of Burn down . [↩]

- Branch, At Canaan'due south Edge. [↩]

- Lyndon Baines Johnson, "Remarks at the Academy of Michigan," May 22, 1964, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, 1964 (Washington, DC: U.South. Regime Printing Office, 1965), 704. [↩]

- Come across, for instance, Wesley G. Phelps, A People'due south War on Poverty: Urban Politics and Grassroots Activists in Houston (Athens: Academy of Georgia Press, 2014). [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Guian A. McKee, "'This Government is with Usa': Lyndon Johnson and the Grassroots State of war on Poverty," in Annelise Orleck and Lisa Gayle Hazirjian, eds., The War on Poverty: A New Grassroots History, 1964–1980 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011). [↩]

- Michael P. Sullivan, The Vietnam War: A Study in the Making of American Foreign Policy (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985), 58. [↩]

- Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Absurd: Business organisation Civilisation, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 7. [↩]

- Brenda Polan and Roger Tredre, The Nifty Mode Designers (New York: Berg, 2009), 103–104. [↩]

- Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York: Penguin, 2011). [↩]

- Peniel Due east. Joseph, ed., The Blackness Power Movement: Rethinking the Ceremonious Rights–Black Power Era (New York: Routledge, 2013), 2. [↩]

- Gordon Parks, "Whip of Blackness Ability," Life (May nineteen, 1967), 82. [↩]

- Joshua Bloom and Waldo East. Martin Jr., Black Confronting Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). [↩]

- In 1974, fishing rights activists and tribal leaders reached a legal victory in United States v. Washington, otherwise known as the Boldt Decision, which declared that Native Americans were entitled to up to fifty per centum of the fish caught in the "usual and accustomed places," equally stated in 1850s treaties. [↩]

- Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Allen Warrior, Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee (New York: New Press, 1997). [↩]

- See, for instance, Juan Gómez-Quiñones and Irene Vásquez, Making Aztlán: Ideology and Culture of the Chicana and Chicano Movement, 1966–1977 (Albuquerque: Academy of New United mexican states Press, 2014). [↩]

- Armando Navarro, Mexican American Youth Organisation: Avant-Garde of the Move in Texas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995); Ignacio M. Garcia, United We Win: The Rise and Fall of La Raza Unida Party (Tucson: Academy of Arizona Mexican American Studies Research Center, 1989). [↩]

- American Women: Written report of the President's Committee the Condition of Women (U.Due south. Section of Labor: 1963), 2, https://www.dol.gov/wb/American%20Women%20Report.pdf, accessed June seven, 2018. [↩]

- Flora Davis, Moving the Mountain: The Women'south Movement in America Since 1960 (Champaign: Academy of Illinois Press, 1999); Cynthia Ellen Harrison, On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues, 1945–1968 (Berkeley: University of California Printing, 1988). [↩]

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: Norton, 1963), fifty. [↩]

- Carol Hanisch, "The Personal Is Political," in Shulamith Firestone and Anne Koedt, eds., Notes from the 2nd Year: Women's Liberation (New York: Radical Feminism, 1970). [↩]

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1962; Linda Lear, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature (New York: Holt, 1997). [↩]

0 Response to "President Jimmy Carter 1977 1950's Fashion Poodle"

Post a Comment